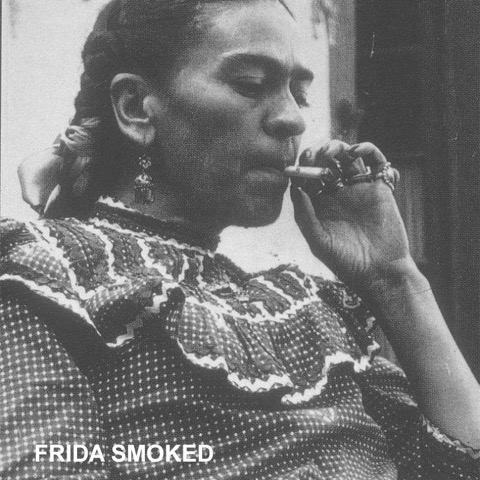

FRIDA SMOKED.

FRIDA SMOKED.

Genesis Belanger, Anne Doran, Celeste Dupuy-Spencer,

Ilse Getz, Irini Miga, and Amanda Nedham

May 13 – June 19, 2016

Reception

Friday, May 13 6-8pm

*

INVISIBLE-EXPORTS is proud to present Frida Smoked, a group exhibition featuring work of women artists and their cigarettes.

* * *

The cigarette was a man’s thing, at first—even though it was thin, white, delicate, and cleaner-smoking than brown-leaf cigars and squat puffy pipes. But smoking at all was unladylike, and so, in 17th century painting, cigarettes appeared only in the hands of prostitutes and other “fallen women”; later, the cigarette became an important marker of Victorian erotic photography. When the femme fatale was photographed cigarette-in-hand in Boston, in 1851, it was a scandal, even for a performer who had made her name as a courtesan; as late as 1908 a woman was arrested for smoking a cigarette in New York City.

But with industrialization came the mass production of cigarettes, and with that came their mass marketing—first using women in advertising to entice men to smoke, then targeting women themselves as customers, once they had joined the workforce en masse during the first world war. Philip Morris sponsored lecture series to teach women, assumed to be incompetent smokers, the proper way to inhale. To truly eliminate the taboo, the American Tobacco Company hired Edward Bernays, the father of public relations, who consulted psychoanalyst A.A. Brill and was told that women were natural smokers, and therefore manipulate-able customers, because of their enduring oral fixation. “Today the emancipation of women has suppressed many of their feminine desires,” he told Bernays. “More women now do the same work as men do. Many women bear no children; those who do bear have fewer children. Feminine traits are masked. Cigarettes, which are equated with men, become torches of freedom.” ‘Torches of Freedom’ became the name of Bernays’ extended campaign, in which, among other efforts, he paid hand-selected women — “while they should be good looking, they should not look too model-y” — to smoke while walking New York’s Easter Sunday parade in 1928. The phrase would be picked up almost 70 years later when American cigarette brands tried to engineer the same gender revolution in emerging markets in Asia and Africa, presenting cigarettes as symbols of freedom, upward mobility, and gender equality.

By then, smoking had long been surpassed as a marker of social ascendency, in America, by something almost like its opposite—a health-and-wellness cult that heralded the purity of women’s bodies even as it insisted that women devote more and more of their own time to remaking and maintaining those bodies for male approval and consumption. And so cigarettes became a different kind of assertive calling card—signaling a different kind of naughty female independence, one made up of disdain for do-gooder nanny-state-ism and self-help mantras peddled in the age of corporate yoga; and driven embrace of youthful indiscretion, downtown depravity, even a sort of sexual nihilism. Of course, all artists smoked—all the good naughty ones anyway.