MARIANNE VITALE | Equipment

MARIANNE VITALE

Equipment

September 9 – October 16, 2016

Reception:

Friday, September 9, 6-8pm

*

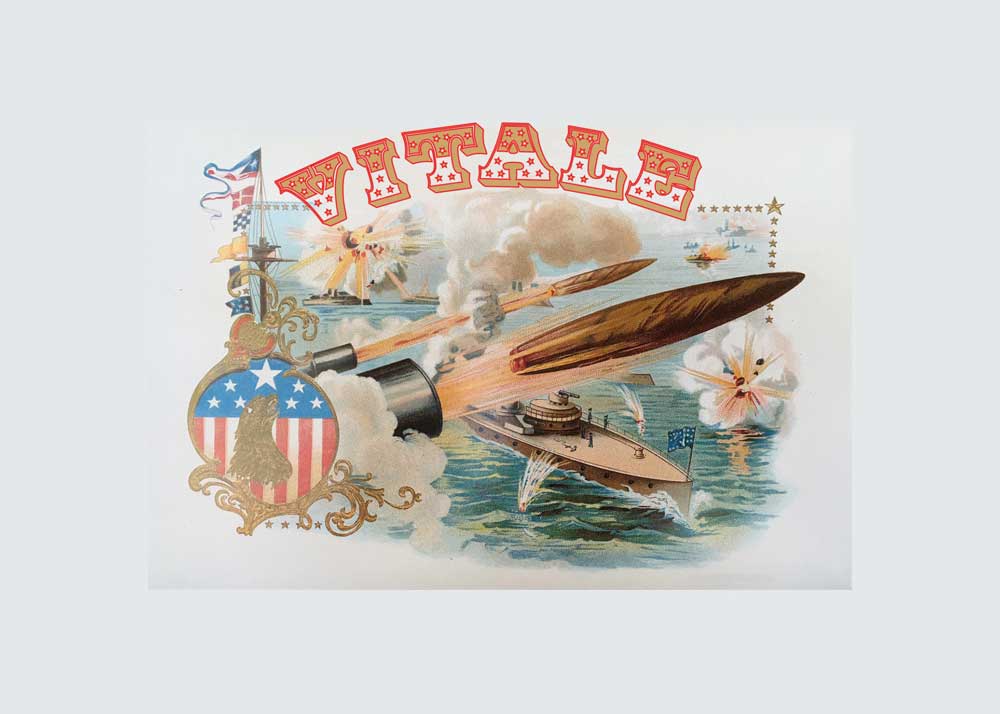

INVISIBLE-EXPORTS is proud to present Marianne Vitale’s “Equipment,” the artist’s first exhibition with the gallery, consisting of a fleet of handcrafted wooden torpedoes, each hand-painted and adorned with a unique insignia.

Since she began her “burning bridges” series almost ten years ago, Marianne Vitale has often been described as an artist working in the language of the frontier, with monumental, large-scale site-specific sculptures that draw on repurposed artifact-materials reanimated from earlier eras and far-flung places: railroad ties, wood bridges, barns. But a better description might be that her work addresses technological frontiers, and thresholds and limits and arrows through time. As Carlo McCormick writes in an upcoming monograph, “Her artworks conjure intermediate places, locations of the indeterminate, interstices in the permanent. They occupy the physical world as substantial destinations of content and form, but they impersonate the journey too well and speak so eloquently of the process that we experience them as somewhere along the way, the location of what is between.”

A torpedo, too, is impermanent, not only because it is designed to explode but because it is really only a torpedo when en route. It gets its power from its in-between-ness. As a concept, the torpedo — a cigar-shaped self-propelled underwater missile — existed for centuries (in 1275, Hasan al-Rammah described “…an egg which moves itself and burns) before it was first successfully built, in 1866. That first “Whitehead Torpedo” was pushed underwater by compressed air, and men have built later models propelled by heat, wet-heat, compressed oxygen, wires, flywheels, electric batteries, gas turbines, and chemical reactions. Before it’s launched, each torpedo is a conceptual fantasy, a vision of water made weapon-ized, imagined by both blockade-runners and their targets, the men with the big boats (“damn the torpedoes, full speed ahead!”). As any kamikaze knows, anything can be a torpedo, so long as it’s sent dramatically in the direction of a ship. And it is a drama: a torpedo chases you. Compared to it, the naval mine — or more pathetically, land mine — looks like a joke of inertness. All a bomb does is drop.

Because weapons of war can no longer be made personally, by hand or bearing any human signature, they must be made personal in order to be given meaning by those who unleash them. Which military men have done ever since the age of modern warfare began, inscribing torpedoes, missiles, even the nose-cones of their bombers and fighter planes with notes to their enemies, cartoons of male swagger (and even its weird counterpart, female sexual availability), and boyish artistic flourishes like superhero logos that look retraced from elementary-school-mural versions of American imperial history. The messages (“To Saddam, this one’s for you! —Craig”) and drawings (a pinup girl winking coyly at the payload, for instance) are an eerie catalogue of the surreally banal, invariably iconographic inner life of military machismo. But who are those messages for? They will never be read, or never again; they want not to be read, only to be written.

* * *

Marianne Vitale (b. 1973) graduated from the School of Visual Arts, NYC (1996). Recent projects include a solo exhibition at Venus, Los Angeles (2016), Contemporary Fine Arts, Berlin (2015); Karma, New York (2015); The Contemporary Austin, Texas (2013); works featured on Chelsea’s High Line, New York (2014); and commissions for Frieze NY and Performa NY (2013). Her work has been exhibited at the Whitney Museum of American Art, White Columns, the Brooklyn Museum, Anthology Film Archives, San Francisco Art Institute; and international venues such as Kunstraum Innsbruck, Austria; Le Confort Moderne, France; Tensta Konsthall, Sweden; UKS, Norway; and Contemporary Art Center of Vilnius, Lithuania. Recent publications include From Here to Nowehere, Karma, NY; Oh, Don’t Ask Why, CFA, Berlin; These Things Are Hard To Say, Yogurt Boys Press, NY; Lost Marbles, Editions Lutanie, Paris; and Train Wreck, Kitto San, New York.