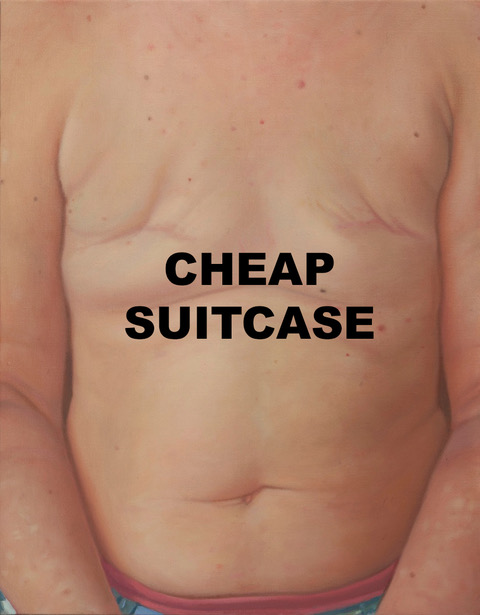

CHEAP SUITCASE

CHEAP SUITCASE

Ron Athey, Genesis BREYER P-ORRIDGE, COUM Transmissions,

Clarity Haynes, Byron Kim, June Yong Lee, Bob Mizer,

Catherine Opie, Ariana Page Russell,

Hannah Wilke, and Rona Yefman

May 19 – June 25, 2017

Reception

Friday, May 19, 6-8pm

*

“The bottom line is that the human species has to realize the human body really is just a cheap suitcase,” BREYER P-ORRIDGE told Douglas Rushkoff in 2007, a sentiment s/he learned from h/er late wife, Lady Jaye. Along the way, any suitcase is going to pick up a few scratches. This exhibition is about those scratches—scars and marks both willful and accidental—and those artists who’ve made use of the skin as parchment, screen, and canvas, a kind of transcript that is memoir and manifesto at once.

Treating the body as a journal has a long history. The practice of tattooing, for instance, began at least as far back as the fourth millennium B.C.E, simultaneous with the invention of writing. In the Samoan tattooing tradition, the biographies and identities of Samoan men were inscribed in elaborate and intricate geometrical patterns that permanently marked their status and experience; in the 20th century, tattooing became the principal record of rank and service in the Russian criminal underworld, transmitted in a kind of public code by an entirely new visual argot. The marks that form the basis of this exhibition are, mostly, of a different kind.

“Scars of E” is composed of four latex “wounds” employed during live performances by COUM Transmissions in 1974-1975—temporary scarifications which were jabbed, stabbed, and sewn up, alongside actual bodily harm, during public actions. BREYER P-ORRIDGE’s Pandrogeny work chronicles the years-long project she and h/er late wife engaged in to merge their identities and bodies into one post-gendered, post-DNA being. Haynes’ portrait series of past-mastectomy torsos crops out the subjects’ head, forcing the viewer to truly read the biography of the body; and Byron Kim’s paintings on linen depict, in exquisitely detailed dreamy compositions, bruises on human skin (themselves both mementoes of violence and projections of the process of healing). Hannah Wilke’s “Why Not Sneeze,” a wire bird cage filled with medicine bottles and syringes, is an abstracted vision of what her body is enduring during her own battle with breast cancer; and Ariana Page Russell — who suffers from dermatographia, a skin disorder that produces an allergy-like reaction in response to the slightest scratch — photographs the dramatic patterns a light striation generations on her skin. The legendary AIDS activist, Ron Athey’s, “Psychic Surgery” brings our attention to the wear and tear our bodies have endured, both from the inside through the viruses we’ve picked up along the way, and our treatment of them: cutting, scraping, scaring, and then watching them heal. Rona Yefman’s “Shanghai Kate’s Back” is a silkscreen print on leather depicting America’s “tattoo godmother” Shanghai Kate Hellenbrand; and Catherine Opie’s “Dyke,” examines tattoo-as-narrative in its most elemental form. And finally the photographs of iconic erotic auteur Bob Mizer famously capture the bodiliness of his subjects, right down to the amputated leg and stick-and-poke tattoos of the hustlers he’d cast in his idiosyncratic erotic fantasias.

The body is a kind of biography too, and it wants to be read.